Big Tick and Ugly Deer

Although I still pine for my former home in the Boston area, I am consoled by the relative proximity of The City, the Big Apple, the place where, if you can make it there, you can make it anywhere, that is to say, New York City. A visit to NYC satisfies me when I'm jonesing for a fix of the urban. It's an easy day trip by train from the central part of the Gaaah-dun State, the neighboring butt of many New Yorkers' jokes and overall contempt, but the source of many home-grown, Jersey Fresh comedians' shtick. I guess you have to possess a good sense of humor to live in Hoboken.

The NJ Transit, PATH and Amtrak trains rumble through some outstanding examples of urban blight. The branch of the NJ Transit system with which I am most familiar makes its way through what epitomized the Garden State in my Midwestern-imprinted mind for a long time: abandoned warehouses, empty, cratered parking lots, grim housing projects, and contaminated marshlands which harbor schools of three-eyed fish. However, the Garden State is appropriately named if one ventures to my little corner of the state. Here are bucolic stretches of farmlands and horsey estates, older villages, pockets of McMansions hemmed in by zoning laws, and woods full of tall trees characteristic of the mid-Atlantic hardwood forest.

The township where I live cherishes and protects its green space, and my immediate neighborhood is surrounded by woods. A preserve and an arboretum are within a mile of my digs. Looking out from my deck, I face a copse of trees whose lacework of leaves, bark and underbrush screen the sight of the other units in the small development. Sweet gums, tulip trees, and maples line the woods' edge. I especially enjoy these surroundings during my early morning perambulations. Currently, these bouts of low key exercise are composed of a lot of walking interspersed with fits of jogging, the intervals of which increase weekly as my fitness slowly but surely returns. Wood thrushes call out in flute-like tones as the sky brightens, and occasionally, screech owls will hoot as they settle down for the day. I've spotted wild turkeys out foraging for their breakfast.

It's tempting to set forth and blaze a trail in these woods, rather than confining myself to asphalt and grass. Back in the Boston area, there are 50 miles of well tended trails around Lincoln and Concord. These trails meander through woods and meadows in conservation land and private property where owners have granted permission for the trails' establishment and maintenance. These were created through the auspices of the Lincoln Land Conservation Trust, and are popular among local long distance runners, who are appreciative of such forgiving surfaces.

Here in Einsteinville, the Autumn Hill Reservation and Herrontown Woods have trails, but they are not as well maintained as the Lincoln, MA system. There is an extensive trail system around the Institute for Advanced Study, but I have yet to check this out. Hopefully, they are more akin to the Lincoln system. Stay tuned.

It's frustrating to see these trail-free expanses of woods along my route, especially since the sparse undergrowth beneath the dense tree canopy would make it appear that creating trails wouldn't be so difficult. However, property owners around here are a possessive bunch as evidenced by the blaring yellow or orange flyers which announce "Posted: Private Property. No trespassing!" tacked to the tree trunks of the along the perimeter of their land. Thus potential lowlife bushwackers are warned, and it seems unlikely that the owners would be willing to let runners and hikers careen through their property. It is not only the gaudy flyers which give me pause when I consider spontaneous trailblazing, but also the sinister devil deer which lurk in the forest.

Yes, I fear the Bambis of Central Jersey. Well, maybe I loathe them. Or fear and loathe them. I admit that I like them as a tenderloin draped in a cognac-based sauce, centered on a fine plate, and with a glass of the old kroovy-like Cab. Sauv. on the side or ground up into "deer balls" then simmered in a ketchup and Welch's Concord grape jelly concoction in a slow cooker. This is a Wisconsin delicacy if ever there was one, and is best washed down with Augsburger Dark.

With the encroachment of humans into their territory, and with no four legged predators to keep their numbers in check, the deer have made hay with their population in Einsteinville, which now stands in the 1100-1300 range in an area estimated to adequately support only 300 of their number. The swollen herd has caused deer-meets-car incidents to increase. Back in Cambridge, I avoided clueless Ivied-out students who wandered out on the streets as I wended my way around Harvard Square. Here I needn't drive in the Ivy students' habitat, but the roads in the township and surrounding countryside take me smack dab into deer territory. My side-of-the-road rapid scanning perception clicks into high paranoid gear as I drive along the Jersey backroads. In a year plus of living here, I've had some close calls, that deer-in-the-headlights scenario, but thankfully, the beasts kept their burning demon eyes at the side of the road instead of directly in front of my car's path. Still, the presence of visible deer in my peripheral vision causes me to flinch and slow down defensively in anticipation of the animal flinging itself in front of my Mini-Cooper.

The deer-car crashes are bad enough, but there is something more insidious which the devil deer bring to the community, and far less obvious, until one starts gathering epidemiological anecdotes from folks in the borough and the township. My elder kid brought home a tidbit of such information gleaned in his high school biology class. His teacher asked the students who among them had contracted Lyme disease, and to raise their hands if they had been infected. My son, still less than 18 months removed from an urban, deerless setting, was one of two out of twenty students in the class who had not contracted the disease. Although we moved from an area of the country where Lyme disease is endemic, deer don't roam freely through the streets of Cambridge, so that part of Middlesex County, MA, is considered low risk for Lyme disease. The wildlife population of the People's Republic boasts skunks, rats, and the odd drunk or junkie here and there, but no Ixodes scapularis lurk on these mammals. Maybe other virulent organisms stake their claim in Cambridge, for example, Larry Summers, but no deer ticks abound along Massachusetts Avenue. I was incredulous at my son's news.

I'm not the only one who has noted the drawbacks of the backyard deer and their eight-legged pals. One of the side effects of living in towns which host Ivy League universities is the presence of Famous People. Yes, there are a number of Famous People who live around here. One of them is Paul Krugman, who is a professor in the Dept. of Economics at Princeton, and a columnist for the New York Times. I like Krugman's writings. He's intelligent as hell, and has a sharp, sometimes biting, sense of humor. As a Famous Person here in Einsteinville, he has something to say about deer:

Oh, Deer

SYNOPSIS: When you're stuck on the computer all day the pesky deer can be your only friends

A troop of about a dozen deer just tromped through the snow in our backyard - a fairly common sight in Princeton (lately I've been seeing this group daily) but still a welcome break when you're slaving away at the computer.

But I'm tormented. I know rationally that deer are a huge nuisance, and even a menace: most of our neighbors have had Lyme disease. I support culling; I think it's irresponsible to feed them.

But they're so adorable ...

Originally published on the Official Paul Krugman Site, 2.18.03 from the Unofficial Paul Krugman website.

Professor Krugman speaks to me. Yes, I admit it. I think the damned things are adorable, too, and really quite graceful except perhaps when launched upon the hood of a vehicle. The critters seem well adapted to their suburban/ex-urban environment, and with no cougars, wolves or even Princeton Tigers to feast upon them, their numbers do not abate. The township's approach to this has been to contract with a culling service. These guys are sharp shooters with guns and with bows as their weapons. By taking on a quasi-lupine role, they attempt to reduce the deer population.

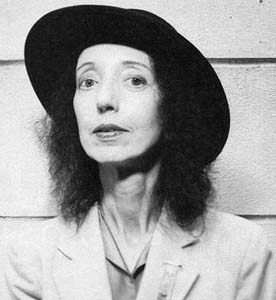

Not surprisingly, the deer herd culling service contract caused a hue and cry among Einsteinville's precious set, including Famous People, who raised objections to the deer herd culling endeavor. One of these Famous People is the accomplished writer, Joyce Carol Oates. Now I recognize that Ms. Oates is a literary lioness of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. In the interest of Educating Myself in contemporary American literature, I made valiant attempts to enjoy her work, but personal tastes led me to other novelists, a couple of whom are noted in my profile. Ms. Kingsolver and Ms. Divakaruni both appear to be hale and hearty women, but for all her formidable intellectualism, Ms. Oates' physical appearance, when extrapolated to an animal totem, recalls nothing other than...a deer. I am not the only one who discerns a connection between the great authoress and this critter.

Oates writes of her studio (from Joyce Carol Oates: In the studio, the American Poetry Review, Jul/Aug 2003)

It's a room much longer than it is wide, extending from the courtyard of our partly glass-walled house in suburban/rural Hopewell Township, New Jersey (approximately three miles from the high-decibel intensity of Princeton) into an area of pine trees, holly bushes and Korean dogwood through which deer, singly, or does-with-fawns, or small herds, are always drifting. Like the rest of the house my study has a good deal of glass: my immediate study area, where my desk is located, is brightly lighted during the day by seven windows and a skylight.

With reference to Oates' essay from which the quote above was taken, Melissa Pritchard, who counts Oates as friend, mentor and confidante, confirms the deer metaphor:

I think of Joyce Carol Oates as a deer, fleet and superbly alert yet always slightly startled by the world, slightly wary, lovely as only swiftness of movement and movement's fluid grace can be, lovely without guile or selfish intent – and her writing, both act and art, like running, too, in running's constant motion, with its eternal impulse to grace of movement and gift of expression, from this, the embodiment of eloquence comes. I am struck by quality of permeability in her as well, absorbing everything, censoring nothing, responding sensitively, empathetically, bravely, and again, if I return to the image of the deer, that agile, surefooted creature arrowing between heaven and earth, aware on all possible levels, subearthly, earthly, celestially, cellularly. She is courageous, unafraid of truths brutal or brilliant, horrifying or divine. And within this deerlike grace unafraid, resides an untrammeled spirit, eternally questing, upheld by the muscled spring of the leg, the pumping of the arms, the breath that sustains, in attunement, in harmony with, the tensile, mercurial mind.

Clearly, Oates identifies with the deer. This is further reinforced by her belief that Princeton exudes "high-decibel intensity." She must indeed be an exquisitely sensitive creature if she describes this sleepy little borough like that. Frankly, given how habituated her Odocoilean pals are to the town, I'm surprised we don't find them queueing up at Thomas Sweet for ice cream or the MacCarter Theatre for a play . The beasts seem far better habituated to the high-decibel life than does the doe-eyed novelist.

Ms. Oates, along with others, argue that the hunters might bag a university student jogging along the trails around the Institute for Advanced Study, and that the community is not given ample warning when the shootings are to take place. My own observation of prominently displayed signs posted around the local preservations, advising that shooters would be out and about during certain months, serves as ample warning to me to take my perambulations to the canal path during said time. Another argument is that stray bullets can travel up to a mile. One would hope that the term "sharpshooter" implies someone who's a better shot than Bernie with a few Budweisers in his belly, but yeah, I can see that as a cause for concern. Net and bolt traps garnered protest among various animal rights activists, including another Famous Person, ethicist and university professor (also Oates' friend), Peter Singer, who said he would prefer a "more humane" method of reducing the herd.

Even though I am callous former agrarian, I would give a nod to the Famous People's objections were it not for Oates' publicized protest against township laws which forbid feeding the damn deer. Yes, humans feeding the deer. It may be a "right" to do what you will in your own domain, but cripes, why act as enablers to the deer's burgeoning population? I can only imagine how the City of Cambridge would react if Alan Dershowitz decided to set out food for the local alley rats.

As Krugman notes, actively aiding and abetting the pesky, albeit adorable, deer is objectionable. Fortunately, the New Jersey courts upheld the ban. Oates' protest to the matter certainly implies that she was feeding the animals. To me, her argument against culling loses some steam since she's interfering with the animals' natural lifestyle by setting out deer chow for them: crumbs for a starving man and all that.

Given the aforementioned Peter Singer's philosophical bent on animal rights, it's perfectly consistent that he would take umbrage at the deer being shot or trapped with nets then "bolted." Captive bolt guns, the same devices employed to kill animals in slaughterhouses, are similarly used to kill the deer after capture. Singer, also on the Princeton faculty, is famous, and infamous, for his statement: "Killing a defective infant is not morally equivalent to killing a person. Sometimes it is not wrong at all." He argues against speciesism with a convincingly pragmatic tone, that is, the life of a human is not necessarily more important than that of say, a mouse, but considers the value of each life on an individual basis. Check out the FAQ section on his web site. His answers to the questions posited are indeed thought-provoking.

Although my views on animal rights certainly are skewed toward species bias, with humans coming out on top, I am simultaneously intrigued and repulsed by Professor Singer's philosophical writings. High on the repulsion list is his review of Dutch biologist Midas Dekker's book, Dearest Pet: On Bestiality. Singer writes that bestiality ought to be illegal only because the act has potential to cause pain and suffering to the animal. For example, porking a chicken invariably results in the hen's death due to internal injury. However, Singer implies in the review that if no harm is done, then why not engage in bestiality? After all, we are as much animals as any other, and to cast horror and shame on the practice of fucking non-human mammals, as long as one doesn't hurt them, is rank speciesism. Again, my human bias runs rampant here. There are many objections to this practice, not the least of which is that a less-than-articulate animal, like a cow or a sheep, cannot give consent to an eager and tumescent farm lad. Zoonoses and the "Ewwwww!" factor also spring to mind. But, hey, there's something for everyone. Why else deck out cows in lingerie?

Yes, I am a speciesist. As a human animal evolved to be an opportunistic ominvore, I eat meat, and I wear leather as the occasion dictates, typically just in the guise of shoes with no leather S&M wear in my closet, since I am a dominatrix only in spirit, and a timid one at that. I don't fuck with non-human animals. I respect others' dietary choices with regard to lacto-ovo-vegetarianism or veganism if presented with reasons of health, dislike of the taste and texture of flesh, or the desire to leave smaller environmental footprint as in the case of veganism. But the rationale of "not eating anything with a face" leaves me cold. That, dear reader, is pure and flagrant kingdomism, i.e. Kingdom Animalia, Kingdom Plantae. As a former student of plant physiology, I can tell you that plants and animals, although very different in many respects, share common features at the molecular level. Plants, albeit non-sentient as far as we know, cf. Day of the Triffids, are as vibrantly alive as any animal. To be truly consistent with my views of the common themes of life at the molecular level, and to avoid kingdomism, I'd have to become a Jain. That's too rigorous a lifestyle for me to adopt, so I may as well eat animal flesh, which has on occasion included venison.

It's less the deer versus vehicle issue that troubles me, statisically speaking, than the high rate of Lyme disease infection in the Garden State. The bug which causes the infection is Borrelia burgdorferi. It's a wiley bacterium since it must evade the host defense systems in order to colonize mammalian tissues. It does this by shifting around its protein expression by differential regulation of its genetic complement. Crafty little bugger. Here's an excellent summary of Borrelia, the tick vector and lifecycle, symptoms of the disease, and much more in the online Textbook of Bacteriology written by Kenneth Todar, Dept. of Bacteriology, at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Quick intervention with doxycycline, the current antibiotic of choice, is in order after a suspected tick bite. The trouble is, in the absence of the characteristic "bull's eye" rash, which only occurs in 60-80% of the bite victims, the symptoms of early stage infection mimic a lot of other infections. Joint pain and neurological symptoms occur in late stage infection, and this is where things can be potentially nasty. It's an unsettling disease. A look at the Center for Disease Control's map of Lyme incidence by county shows a lot of deep blue in this region. In the interest of full public health disclosure, the incidences of gonorrhea and clamydia infections are higher in Mercer County, but Lyme is third. Mammals other than deer, like the white footed mouse, and birds carry the tick, but these hoofed critters are prime suspects since adult ticks preferentially feed upon white tailed deer. Quoted from K. Todar's article:

A relationship has been observed between the abundance of deer and the abundance of deer ticks in some parts United States. Reducing and managing deer populations in geographic areas where Lyme disease occurs may reduce tick abundance.

In the interest of "fairness," here is the Mercer County Deer Alliance web site which has not been updated for two years. The deer advocates support non-lethal means of reducing the population, and in fact, the culling contractor instituted a pilot program in which the does are brought down with tranquilizer guns, then tagged with a device which releases a deer contraceptive. So the deer can boink all they wish, and not reproduce. This is a pretty nifty idea, but it is more costly than lethal culling. The other tactic is to control the ticks themselves. These ticks like brush, so removing such is an option, but undoubtedly, those who wish to leave the Bambis be will also strenuously object to pesticides liberally applied to the woods.

When I was a kid, I remember how sad I was when Bambi's mother was killed by the hunter in the Disney movie. Oh, fawns, cartoon characters or breathing, long limbed beasties, seemed so cute then. Now, when I spot a real-life doe, buck or fawn, I not only see a graceful creature, but a walking bundle of zoonosis. And I would cheer raucously should I again view Bambi's mother's cinematic demise. Goddamn devil deer.

----------------------------------------

Doc Bushwell's Let's Have Fun with Science Glossary:

zoonosis, pl.zoonoses: a disease in animals which can be transmitted to humans.